Unit 4: Imperfect Competition

| Created | |

|---|---|

| Tags |

4.1 - Introduction to Imperfectly Competitive Markets

Market Structures

Perfect Competition

- Many firms in competition with each other

- Goods being sold are identical, with no product differentiation

- Individual firms have no control over prices, they are called "price takers"

- Low barrier to entry (solely startup cost)

- Well informed buyers and sellers

Monopolistic Competition

- Many firms in competition with each other

- There is some amount of differentiation between products

- Individual firms have no control over prices, they are called "price takers"

- Low barrier to entry (solely startup cost)

- Monopolistic competitors use non-price competition (Advertising, giveaways, promotions, etc.)

Oligopoly

- Few firms control the market

- Firms have a strong control over price, and frequently collude to set prices

- Firms can also engage in price wars and predatory pricing

- Medium barrier to entry

- Price Leadership: Unofficial collusion where firms follow a single firm when that firm changes their price

Monopoly

- One firm has absolute control over the market

- No variety of goods

- Firm is a price maker, they are able to set the price to whatever they want

- High barrier to entry

Price Control or Price “Makers”

All imperfectly competitive firms exert some control over price. This ability comes from either the type of product they sell OR the amount of competition.

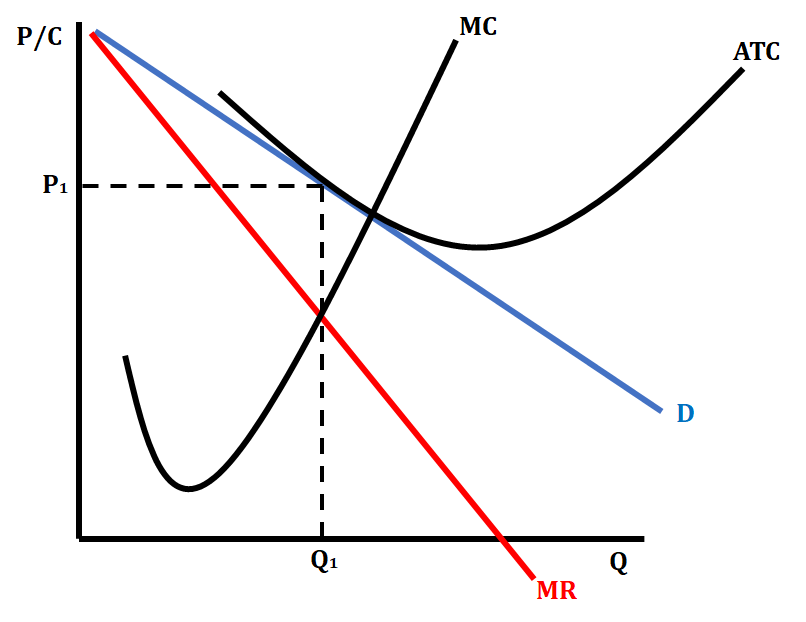

Price-making firms face a downward-sloping demand curve, greater than the marginal revenue curve.

Why Imperfectly Competitive Firms are Inefficient

Defining Efficiency

- Allocative Efficiency (): The price of a good should be equal to the value of the resources (land, labor, capital) used to produce it. Also known as the Socially Efficient quantity of output.

- Productive Efficiency (): The least costly production techniques are used.

In perfect competition, a firm’s . Therefore, perfectly competitive firms are also 100% efficient.

The same is not true for imperfectly competitive firms, as they are able to make a profit in the long run.

4.2 - Monopolies

A monopoly is a firm that is the sole seller of a product without close substitutes.

Why Monopolies Arise

The main cause of monopolies is barriers to entry—other firms cannot enter the market.

Three sources of barriers to entry:

- A single firm owns a key resource. Eg: DeBeers owns most of the world’s diamond mines.

- The government gives a single firm the exclusive right to produce the good.

- Natural monopoly: a single firm can produce the entire market at a lower cost than could several firms.

For a monopoly, the curve slopes downwards as they have huge and small .

Monopoly vs. Perfect Competition: Demand Curves

In a competitive firm, the market supply curve is perfectly elastic.

A monopolist is the only seller, so it faces the market demand curve. To sell a larger , the monopoly must reduce its .

In a monopoly, and .

Understanding the Monopolist’s MR

- Increasing has two effects on revenue:

- Output effect: higher output raises revenue

- Price effect: lower price reduces revenue

- To sell a larger , the monopolist must reduce the price on all the units it sells.

- Hence, .

- could even be negative if the price effect exceeds the output effect.

Profit Maximization

- Like a competitive firm, a monopolist maximizes profit by producing the quantity where .

- Once the monopoly has its price maximizing quantity of output, it will identify the price consumers are willing to pay from the demand curve at that quantity .

- Because this must be greater than the point, monopolies are guaranteed to make long run profits.

A Monopoly Does Not Have an Curve

A competitive firm:

- takes as given

- has a supply curve that shows how its depends on

A monopoly firm:

- is a “price-maker”, not a “price-taker”

- does not depend on

- and are jointly determined by , , and the demand curve.

Because of this, there is no supply curve for monopolies.

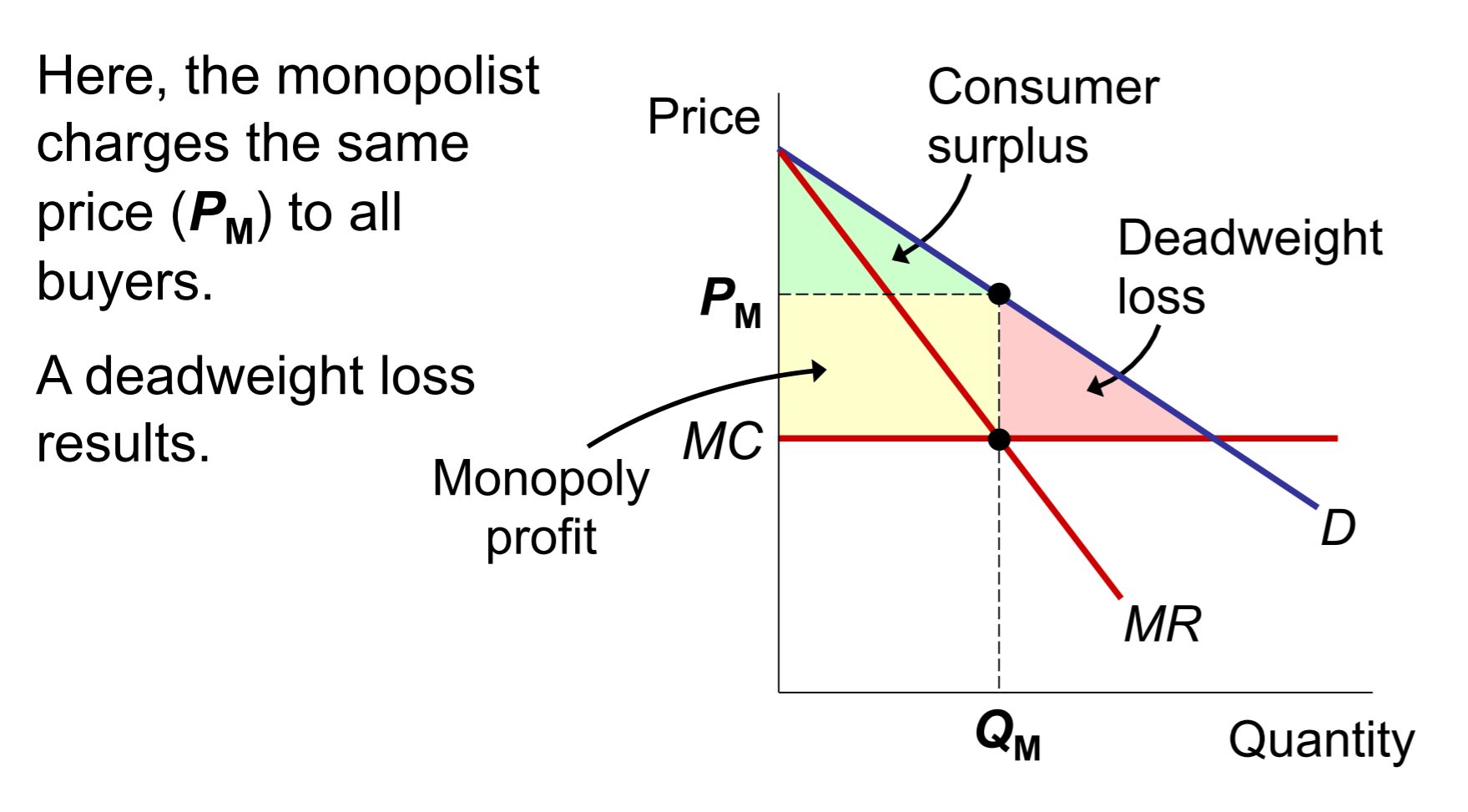

The Welfare Cost of Monopoly

The value to buyers of an additional unit, , exceeds the cost of the resources needed to produce that unit, . This creates a deadweight loss, which could be recouped were the market in perfect competition. This takes away from the consumer surplus and the total surplus, and brings some additional producer surplus.

In perfect competition, , but in a monopoly, . The deadweight loss created by the monopoly is the difference between and which would not be present in perfect competition.

Public Policy towards Monopolies

- Increasing competition with antitrust laws

- Ban some anticompetitive practices, allow govt to break up monopolies.

- e.g., Sherman Antitrust Act (1890), Clayton Act (1914)

- Regulation

- Government agencies set the monopolist’s price

- For natural monopolies, at all , so marginal cost pricing would result in losses.

- For these firms, regulators might subsidize the monopolist or set for zero economic profit.

- Public ownership

- Example: US Postal Service

- Problem: Public ownership is usually less efficient since no profit motive to minimize costs

- ^ bullshit

- Doing nothing

- The foregoing policies all have drawbacks, so the best policy may be no policy.

- ^ also bullshit

- The foregoing policies all have drawbacks, so the best policy may be no policy.

Conclusion

- In the real world, pure monopoly is rare.

- Yet, many firms have market power, due to:

- selling a unique variety of product

- having a large market share and few significant competitiors

- In many such cases, most of the results from this chapter apply, including:

- markup of price over marginal cost

- deadweight loss

4.3 - Price Discrimination

- Discrimination: treating people differently based on some characteristic, e.g. race or gender.

- Price discrimination: selling the same good at different prices to different buyers.

- The characteristic used in price determination is willingness to pay (WTP):

- A firm can increase profit by increasing the price for buyers with a higher WTP.

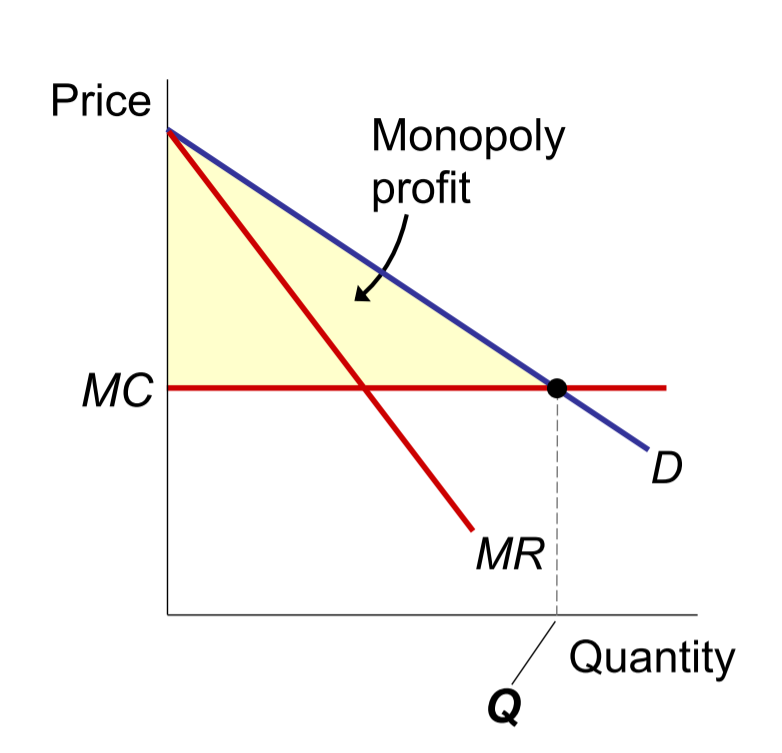

Perfect Price Discrimination vs. Single Price Monopoly

In a single price monopoly, a firm charges a fixed price for all buyers. This price is greater than the MC for the good, and therefore results in a deadweight loss.

With perfect price discrimination, the monopolist produces the competitive quantity, but instead of charging a fixed price, charges every individual buyer their WTP.

In this instance, the monopolist captures all CS as profit. The area which was a deadweight loss for a single-price monopoly instead becomes profit for the monopolist.

Price Discrimination in the Real World

- Perfect price discrimination is not realistic in the real world:

- No firm knows every buyer’s WTP

- Buyers do not reveal it to sellers

- So, firms divide customers into groups based on some observable trait that is likely related to WTP, such as age.

4.4 - Monopolistic Competition

Monopolistic competition: many firms sell similar, but not identical, products.

Characteristics

- Many sellers

- Product differentiation

- Free entry and exit

Examples

- apartments

- books

- bottled water

- clothing

- fast food

- night clubs

Comparing Perfect and Monopolistic Competiton

- Number of sellers: both perfect and monopolistic competition have many sellers

- Free entry and exit: both

- Long-run economic profits: zero for both, as a result of the freedom to enter and exit the market freely

- Firms sell: identical products in perfect competition, differentiated products in monopolistic competition

- Market power: none for perfect competition, some for monopolistic competition as they have the ability to create product differentiation. Location can actually be an important form of “product differentiation” for firms in monopolistic competition.

- curve facing firm: horizontal in perfect competition, downward sloping in monopolistic competition. This is because firms in monopolistic competition have some market power.

Comparing Monopoly and Monopolistic Competition

- Number of sellers: one in a monopoly, many in monopolistic competition

- Free entry/exit: no for monopoly, yes for monopolistic competition

- Long-run economic profits: positive for a monopoly, zero for monopolistic competition

- Firm has market power?: yes for both, though monopolies obviously have more power

- curve facing firm: both are downward sloping, but monopolies actually face the market demand curve, while firms in monopolistic competition all have unique demand curves.

- Close substitutes: none for monopoly, many for monopolistic competition

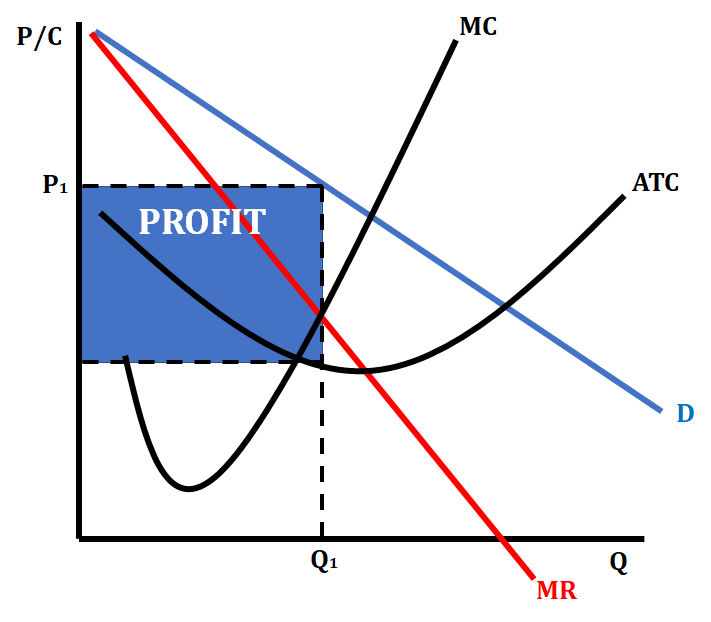

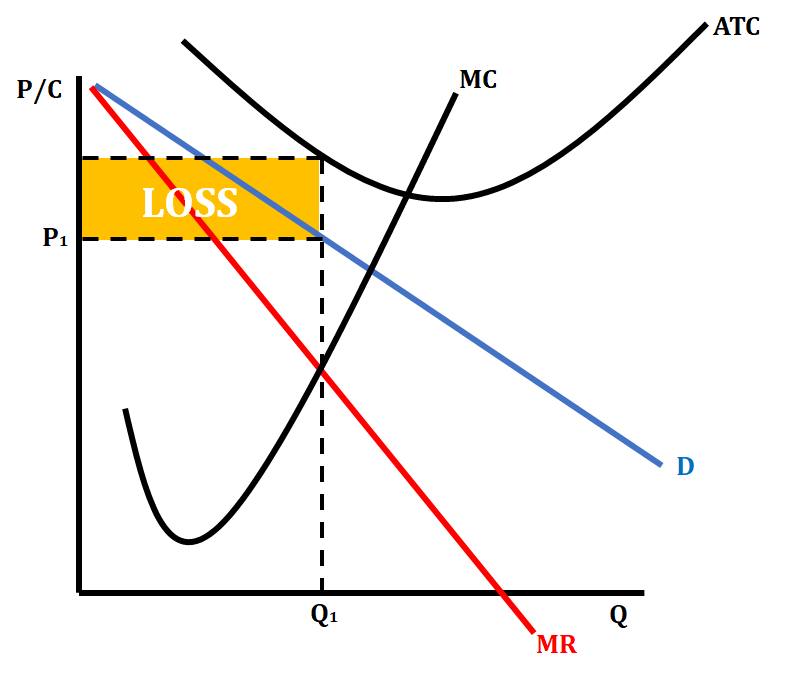

Monopolistic Competition in the Short Run

At each , . To maximize profit, the firm produces where , and then uses the curve to set . The area of profit or loss is the difference between and , times the quantity produced at the profit maximizing quantity of output.

Going from Short Run to Long Run

In the short run, firms in monopolistic competition behave very similarly to monopolies.

In the long run, however, entry and exit in monopolistic competition drive economic profit to zero, similarly to perfect competition.

- When monopolistic firms earn a profit in the short run, it compels firms to enter which provides more close substitutes and less market share for the existing firms. This leads to the demand and curves shifting left together so that the demand curve becomes tangent with .

- When monopolistic firms earn a loss in the short run, it compels firms to exit which provides less close substitutes and more market share for the existing firms. This leads to the demand and curves shifting right together so that the demand curve becomes tangent with .

Monopolistic Competition in the Long Run

In the long run, the economies of scale portion of the curve will become tangent to the demand curve at the profit-maximizing price level. This results in a zero-profit equilibrium for firms in monopolistic competition.

Notice that the firm charges a markup of price over marginal cost and does not produce at minimum .

Why Monopolistic Competition is Less Efficient than Perfect Competition

- Excess capacity

- The monopolistic competitor operates on the downward-sloping part of its curve, therefore producing less than the cost-minimizing output.

- Under perfect competition, firms produce the quantity that minimizes .

- Markup over marginal cost

- Under monopolistic competition, .

- Under perfect competition, .

Monopolistic Competition and Welfare

- Monopolistically competitive markets do not have all the desirable properties of perfectly competitive markets.

- Because , the market quantity is below the socially efficient quantity.

- Yet, it is not easy for policymakers to fix this problem: firms earn zero profits, so cannot require them to reduce prices.

- Number of firms in the market may not be optimal, due to external effects from the entry of new firms:

- The product-variety externality: surplus consumers get from the introduction of new products.

- The business-stealing externality: losses incurred by existing firms when new firms enter market.

- The inefficiencies of monopolistic competition are subtle and hard to measure. No easy way for policymakers to improve the market outcome.

Advertising

- In monopolistically competitive industries, product differentiation and markup pricing lead naturally to the use of advertising.

- In general, the more differentiated the products, the more advertising firms buy.

- Economists disagree the social value of advertising.

Critiques of Advertising

- Society is wasting the resources it devotes to advertising.

- Firms advertise to manipulate people’s tastes.

- Advertising impedes competition—it creates the perception that products are more differentiated than they really are, allowing higher markups.

Defense of Advertising

- It provides useful information to buyers.

- Informed buyers can more easily find and exploit price differences.

- Thus, advertising promotes competition and reduces market power.

Advertising as a Signal of Quality

A firm’s willingness to spend huge amounts on advertising may signal the quality of its product to consumers, regardless of the content of ads.

- Ads may convince buyers to try a product once, but the product must be of high quality for people to become repeat buyers.

- The most expensive ads are not worthwhile unless they lead to repeat buyers.

- When consumers see expensive ads, they think the product must be good if the company is willing to spend so much on advertising.

Brand Names

In many markets, brand name products coexist with generic ones. Firms with brand names usually spend more on advertising and charge higher prices for the products. They are able to charge more by creating a brand image.

Critique of Brand Names

- Brand names cause consumers to perceive differences that do not really exist.

- Consumers’ willingness to pay more for brand names is irrational, fostered by advertising.

- Eliminating govt protection of trademarks would reduce influence of brand names, result in lower prices.

Defense of Brand Names

- Brand names provide information about quality to consumers.

- Companies with brand names have incentive to maintain quality, to protect the reputation of their brand names.

4.5 - Oligopoly and Game Theory

Measuring Market Concentration

- Concentration ratio: the percentage of the market’s total output supplied by its four largest firms.

- The higher the concentration ratio, the less competition.

- This chapter focuses on oligopoly, a market structure with high concentration ratios.

Oligopoly

- Oligopoly: a market structure in which only a few sellers offer similar or identical products.

- Strategic behavior in oligopoly: A firm’s decisions about or can affect other firms and cause them to react. The firm will consider these reactions when making decisions.

- Game theory: the study of how people behave in strategic situations.

- Collusion: an agreement among firms in a market about quantities to produce or prices to charge

- Cartel: a group of firms acting in unison

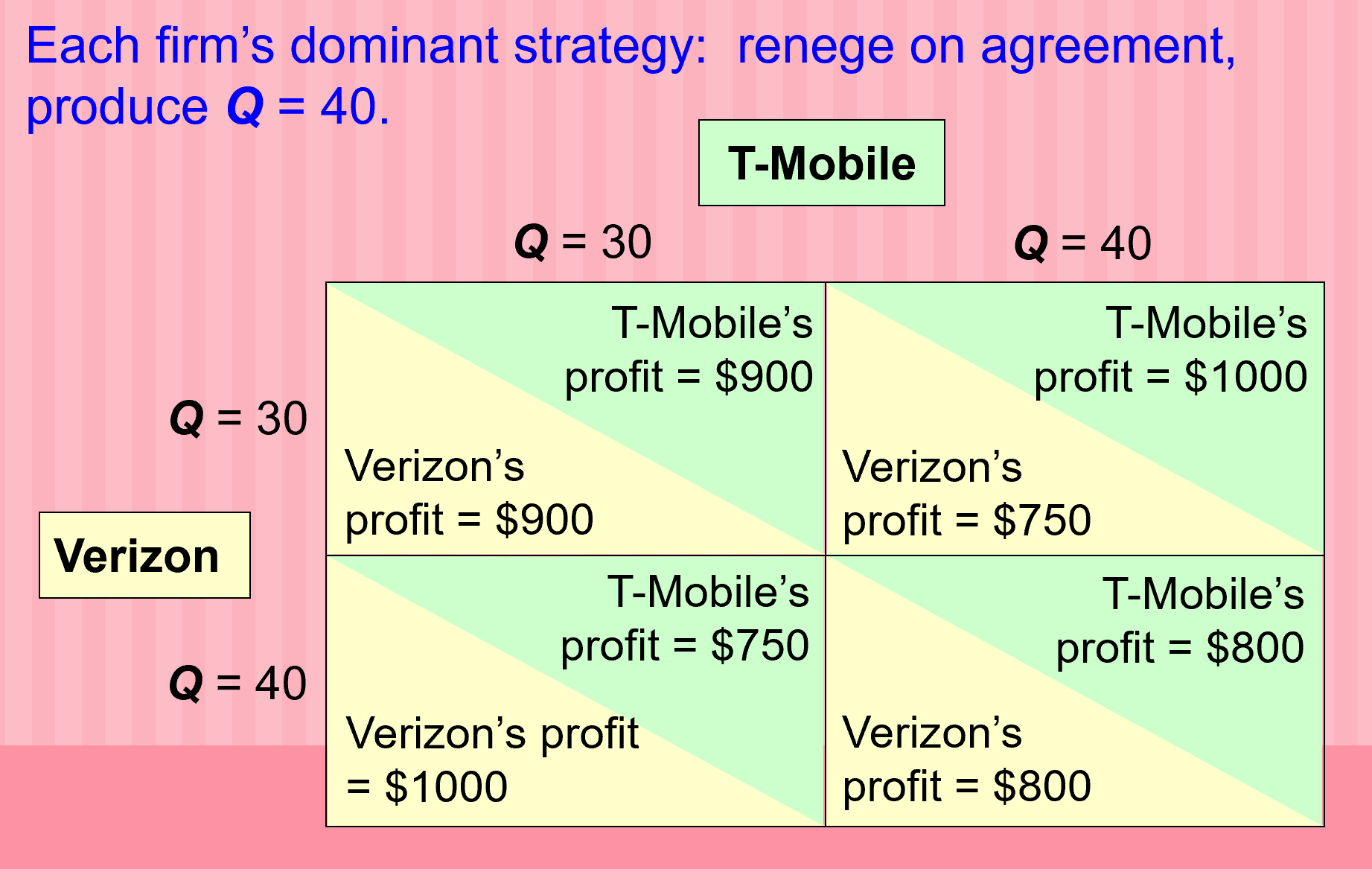

Collusion vs. Self-Interest

- In a duopoly, both firms would be better off if both stick to the cartel agreement.

- But each firm has an incentive to renege on the agreement.

- Lesson: It is difficult for oligopoly firms to form cartels and honor their agreements.

The Equilibrium for an Oligopoly

- Nash equilibrium: a situation in which economic participants interacting with one another each choose their best strategy given the strategies that all the others have chosen.

A Comparison of Market Outcomes

When firms in an oligopoly individually choose production to maximize profit,

- Oligopoly is greater than monopoly but smaller than competitive .

- Oligopoly is greater than competitive but less than monopoly .

The Output and Price Effects

- Increasing output has two effects on a firm’s profits:

- Output effect: If , increasing output raises profits.

- Price effect: Raising output increases market quantity, which reduces price and reduces profit on all units sold.

- If output effect > price effect, then the firm increases production.

- If price effect > output effect, then the firm reduces production.

The Size of the Oligopoly

As the number of firms in the market increases,

- the price effect becomes smaller

- the oligopoly looks more and more like a competitive market

- approaches

- the market quantity approaches the socially efficient quantity

Game Theory

- Game theory helps us understand oligopoly and other situations where “players” interact and behave strategically.

- Dominant strategy: a strategy that is best for a player in a game regardless of the strategies chosen by the other players.

- Prisoners’ dilemma: a “game” between two captured criminals that illustrates why cooperation is difficult even when it is mutually beneficial.

Oligopolies as a Prisoners’ Dilemma

- When oligopolies form a cartel in hopes of reaching the monopoly outcome, they become players in a prisoners’ dilemma.

- Our earlier example:

- T-Mobile and Verizon are duopolists in Smalltown.

- The cartel outcome maximizes profits: Each firm agrees to serve Q = 30 customers.

- Both firms will end up choosing their dominant strategy, causing a loss for both.

Other Examples of the Prisoners’ Dilemma

Ad Wars

Two firms spend millions on TV ads to steal business from each other. Each firm’s ad cancels out the effects of the other, and both firms’ profits fall by the cost of the ads.

Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC)

Member countries try to act like a cartel, agree to limit oil production to boost prices & profits. But agreements sometimes break down when individual countries renege.

Arms Race between Military Superpowers

Each country would be better off if both disarm, but each has a dominant strategy of arming.

Common Resources

All would be better off if everyone conserved common resources, but each person’s dominant strategy is overusing the resources.

Prisoners’ Dilemma and Society’s Welfare

- The noncooperative oligopoly equilibrium:

- Is bad for oligopoly firms, preventing them from achieving monopoly profits

- Is good for society:

- is closer to the socially efficient output

- is closer to

- In other prisoners’ dilemmas, the inability to cooperate may reduce social welfare.

- e.g. arms race, overuse of common resources

Why People Sometimes Cooperate

- When the game is repeated many times, cooperation may be possible.

- These strategies may lead to cooperation:

- If your rival reneges in one round, you renege in all subsequent rounds.

- “Tit-for-tat”: Whatever your rival does in one round (whether renege or cooperate), you do in the following round.

Public Policy Toward Oligopolies

- In oligopolies, production is too low and prices are too high, relative to the social optimum.

- Role for policymakers: Promote competition, prevent cooperation to move the oligopoly outcome closer to the efficient outcome.

Controversies over Antitrust Policy

- Most people agree that price-fixing agreements among competitors should be illegal.

- Some economists are concerned that policymakers go too far when using antitrust laws to stifle business practices that are not necessarily harmful, and may have legitimate objectives.

- We consider three such practices:

- Resale Price Maintenance (“Fair Trade”)

- Occurs when a manufacturer imposes lower limits on the prices retailers can charge.

- Is often opposed because it appears to reduce competition at the retail level.

- Yet, any market power the manufacturer has is at the wholesale level; manufacturers do not gain from restricting competition at the retail level.

- The practice has a legitimate objective: preventing discount retailers from free-riding on the services provided by full-service retailers.

- Predatory Pricing

- Occurs when a firm cuts prices to prevent entry or drive a competitor out of the market, so that it can charge monopoly prices later.

- Illegal under antitrust laws, but hard for the courts to determine when a price cut is predatory and when it is competitive & beneficial to consumers.

- Many economists doubt that predatory pricing is a rational strategy:

- It involves selling at a loss, which is extremely costly for the firm.

- It can backfire.

- Tying

- Occurs when a manufacturer bundles two products together and sells them for one price (e.g., Microsoft including a browser with its operating system)

- Critics argue that tying gives firms more market power by connecting weak products to strong ones.

- Others counter that tying cannot change market power: Buyers are not willing to pay more for two goods together than for the goods separately.

- Firms may use tying for price discrimination, which is not illegal, and which sometimes increases economic efficiency.

- Resale Price Maintenance (“Fair Trade”)